Stages of “collective thinking and suffering” as reflected in Innokentii Annensky’s Kiparisovyi larets [The Cypress Casket] (Trilistnik prizrachnyi [A Ghostly Trefoil])

Shevtchuk Julia Vadimovna Bashkir State University

Annensky’s lyricism is an original creative representation of the inseparability of the intellectual and the emotional in the author’s life. The poet’s “endless intimacy” (V. Rozanov) [15] stems from his actual spiritual experience of painfully realizing the place of self in the world and of the world in self. This was an attitude of a man of many hats (a high-ranking official and an author) and a person highly attuned to the feelings of “the other.” I suppose, Annensky had an affinity for the intellectual lyricism of Dostoyevsky, who had sieved through a variety of ideas and produced a “psychological wonder” — the special “tone,” which V. Rozanov described in his article Tchem nam dorog Dostoyevsky? K 30-letiiu so dnia yego kontchiny [Why is Dostoyevsky important to us? Towards the 30th anniversary of his death] as follows: “<…> he had a little of ‘the world’s soul’ in him, a particle of which is certainly present ‘in me, too,’ just as it is present ‘in everyone’”[15]. It was in Dostoyevsky’s oeuvre that Annensky the literary critic discovered the method we believe should be applied to analyzing his own poetry — that of symbolic consciousness.

А. Blok observed in his 1906 review of Annensky’s first book, Tikhie pesni [Quiet songs] (1904): “Of note is the translator’s ability to render various emotions” [4, 620]. Annensky’s younger contemporary spoke of his translations from the French literature, but exactly this ability would later on determine the distinctive lyricism of The Cypress Casket and influence the meaning and the structure of the final collection of poems by one of the most enigmatic Russian symbolists. N. Gumilyov completed Blok’s thought by remarking that Annensky “discovers the links between the fate of the Danish prince and ours” [9, 173]. Indeed, the poet is capable of presenting a remote experience of “someone else’s” as one’s own, unforgotten, close to heart, even “our own.” Annensky believed that by the early twentieth century, “the phantom of creative individuality had almost expired” in European culture. He wrote, “Therefore, allow me not to dwell on how the centre of the wondrous needs to shift from the collapsed chambers of individual intuition to the vessel of collective thinking and suffering <…>” [2, 477].

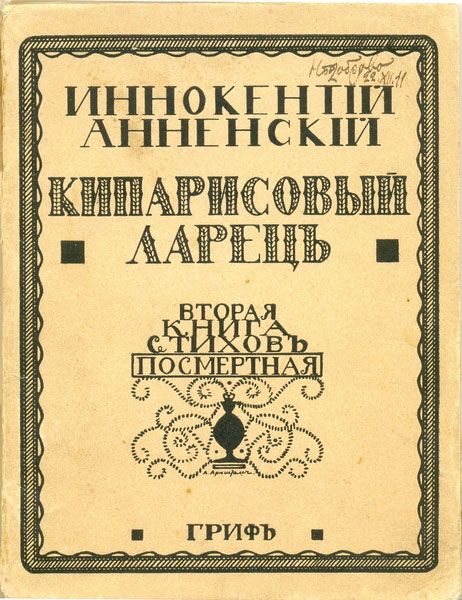

In The Cypress Casket (1910), published immediately after the author’s death, Annensky undertakes an attempt to “save in oneself” the basic forms of human response to the outside world (emotions and sentiments defining one’s worldview) “by making them part of oneself” [2, 5]. These forms are a product of a specific era’s way of thinking: they slowly accumulate in the cultural “memory” and eventually solidify into established formulas. The “absolutes” of conscience are a liability for a thinker who is aware of their restraints. Annensky wrote about the heavy burden weighing down his contemporaries: “None of us stands a chance to depart from those ideas, which, like an inheritance and a duty to the past, become part of our soul right when we are about to enter a conscious life” [2, 411]. However, in reality the burden of the “legacy” of past ideas and emotions is felt at every step of the way. This “legacy” builds up around some timeless situations — certain “nerve-knots” connecting instincts and thoughts, flesh and soul, “life” and “conscience”. For the poet, a man’s psychic reaction to nature and gender relations forms an essential “starting point,” whereas human creativity, the sense of ethics and aesthetics and, accordingly, an understanding of morals and the art, are a moving force.

The Cypress Casket consists of three sections. In the sequence of “trefoils,” the poet follows the principle of consecutive progression from mythical times to modernity. Neither the realities of material life, nor the socio-historical events of European history are of interest to him: rather, his focus is on the development of collective sentiments. In the Skladni [Folding Icons], the principal symbol is the conscience (with emphasis on the subconscious, with its hodge-podge of instincts and fears) of the poet’s contemporary, that has absorbed experiences of generations upon generations and whose own, intrinsically valued worldview has distanced it from nature. In the Razmetannye list’ia [Scattered Leaves], the author “restores” to the subject a sense of “life’s substratum” [2, 206]. Annensky thus tries to overcome the tragedy of self-consciousness. The source of suffering shifts from the substance of a word (Nevozmozhno [Impossible]) to a heartfelt memory of the past (Sestre [To My Sister]), to the sound of dripping water (Toska medlennykh kapel’ [The Melancholy of Slowly Falling Drops]), to random voices in the street (Nervy: Plastinka dlya grammofona [The Nerves: A Phonograph Record]), etc. However, the character’s perception cannot rid itself of thoughts, which detract from the pure immediacy of contact with the material world.

To my mind, the developmental dynamics of the artistic unity known as the Trefoils allow one to distinguish several groups of trefoils representing the three phases of experiencing the world and self in the history of European culture. First, consciousness is born in the immediate connection with nature. Then, creative abilities and the inner world develop. Lastly, the “ego” falls away from the world of things and people. The collective conscious initially incorporated mythological concepts, which underlined the ancient — indissoluble — bonds between humans and nature. Later on, images borrowed from the art made their appearance (Don Juan, Faust, Parzival). Annensky succeeds in conveying many a person’s state of mind by turning the Trefoils into a meeting place of diverse “axiological contexts”, viewpoints, voices. One of the first structures to develop in human conscience is the perception of discrete lapses of time (eternity vs. a certain length of time vs. a moment) and that of space configuration (wherein an opposition of “inside” and “outside” plays an important role). According to Annensky, conscience steadily gained in sophistication due to the discovery of perspective, relativity of motion, distinction between the biological time and the subjective sense of time. The Trefoils abound with references to the philosophical doctrines and scientific theories that influenced human perception of the world (Plato, La Mettrie, Pascal, Descartes) and literary works preserving ideological and emotional characteristics of their time. Their authors are not explicitly named: rather, their presence is felt through quotations, allusions, reminiscences; also, poetic genres of iamb, sonnet, and ballad serve as peculiar vehicles of experience. Especially interesting, from a philological viewpoint, is Annensky’s attempt to employ linguistic formulas capable of preserving and transmitting the “memory” of past generations’ experiences (for instance, in the Trilistnik obrechenosti [Trefoil of Resignation], construction of a phrase follows the syntactic scheme of Lermontov’s Parus [The Sail]).

One may see the Trilistnik prizrachnyi [Ghostly Trefoil] as central to the second group of trefoils, which artistically express the anguish of a man whose idealistic constructs stand in contradiction to the natural order of things. Annensky finds it paradoxical, that the fuller our inner life, the more insistently it tries to achieve its artificially created Ideal in real life. Thought turns the world into a homogenous substance, while at the same time promoting a new law of internal action to counterbalance external inaction: a coincidentia oppositorum (Lat., “unity of opposites”). The trefoil bespeaks Annensky’s recourse to the alchemical practices and philosophical doctrines of the Renaissance (Nicholas of Cusa, Giordano Bruno).

The ghosts of Hamlet, Faust, and the warlock Finn from Pushkin’s Ruslan i Liudmila [Ruslan and Ludmila] show up in this mini-cycle as symbols of experiencing the incompleteness and finiteness of the “sublunar realm”, as symptoms of man’s impossible desire not only to conceive a dream, but to see it come true. In one of his articles, Annensky defined this as “Hamlet’s problem” (Hamlet, 1907): for Hamlet, “life can no longer be either active or enjoyable” [2, 163]. He continues, “This free spirit cannot even recall the ghost’s words, since it is not up to him to turn them into an impulse — the only thing that determines his actions. <…> However, Shakespeare’s genius, as poet and actor, does not leave us any doubts in Hamlet’s personhood. The crazier the medley of contradictions referred to by the name of Hamlet, the more attractive to us is his vitality” [2, 169]. Man’s inner life is natural, real, valuable, but it is an objectivity of a certain kind — one that constantly strives for at least a short-lived fulfillment in reality.

Importantly, the primary literary doppelganger of the lyrical “ego” in The Ghostly Trefoil is Faust — a historical person from the Renaissance and, at the same time, a shadowy figure which embodies the world outlook of generations of Europeans and reflects medieval beliefs and superstitions — the folklore image of a “warlock,” whose roots go back to the early Christianity. Goethe had made his protagonist a vehicle of his own life-long intellectual suffering, and so in his agony Goethe’s Faust towers over the learning of alchemists and mechanists, rationalists and idealists — all those who painstakingly labored over a problem of transforming the world not only through thought, but also through action, and were tempted to carry out most incredible ideas.

Two souls, alas! reside within my breast,

And each withdraws from, and repels, its brother.

One with tenacious organ holds in love

And clinging lust the world in its embraces;

The other strongly sweeps this dust above

Into the high ancestral spaces. [Trans. Bayard Taylor]

In order for us to understand the connection between Goethe’s Faust with the problems of the preceding Trilistnik dozhdevoi [The Rainy Trefoil], the scene from Faust needs to be recalled, where the protagonist experiences difficulty translating the Greek logos in the Gospel of John. The scholar’s tenacious mind queries that which is hidden behind the illusion of the text and which at one point must have been Life itself — the principal creation of God and, accordingly, the foundation of the restless human Thought. Let us note that for Goethe the thinker and natural philosopher, the notion of “metamorphosis” had a special meaning: the scholar imagined the world as an assemblage of living forms organically developing at every level of being — in other words, the world consisted of metamorphoses. (Goethe traced the dialectics of the organic primarily in plant and human forms; particularly his independent discovery in 1784 of the intermaxillary bone confirmed man’s relation to the animal world).

’Tis written: “In the Beginning was the Word.”

Here am I balked: who, now can help afford?

The Word? —impossible so high to rate it;

And otherwise must I translate it.

If by the Spirit I am truly taught.

Then thus: “In the Beginning was the Thought”

This first line let me weigh completely,

Lest my impatient pen proceed too fleetly.

Is it the Thought which works, creates, indeed?

“In the Beginning was the Power,” I read.

Yet, as I write, a warning is suggested,

That I the sense may not have fairly tested.

The Spirit aids me: now I see the light!

“In the Beginning was the Act,” I write. [Trans. Bayard Taylor]

In the poem Nox vitae (Lat., “the night of life”) Annensky describes a protagonist who is losing touch with the real movement in the world and perceives internal peace and withdrawal as death (the entire poem builds on the titular metaphor). A researcher I. Smirnov rightly observes, “Annensky’s artistic thinking was mostly metonymic”: for him, all elements in the world are contiguous [17, 79]. “Non-differentiation of the internal and external is a particular case of the more general isomorphism that Annensky applied to the parts and categories of the universe; in the Nox vitae top becomes one with bottom, night with death, the world is homogeneous throughout” [17, 78]. One’s intensive inner life drives one away from the “azure” of the world, replacing it with the “lunar cold” of self-conscience. Annensky’s metonymy is a typical form of his intellectual experience: the elements of metonymy and the process of restoring unity at a qualitatively new level are part and parcel of the lyrical plotline. In the first poem, the author portrays how one’s mind throws upon the world a “veil” of idiosyncratic perception, thus becoming capable of introspection. The internal progression of thought corresponds to the shift from day to night: as twilight slowly morphs into darkness and peace, the analytic differentiation («Но… ветер… клены… шум вершин») gives way to synthesis, a search for connections between parts («Как странно слиты сад и твердь»). The narrator pursues the enigma of unity by moving “inwards” and retreating from sensual discernment. The first stanza still bears traces of life itself, of objects touching each other, attracting each other: here, buckthorn berries give bloodless jasmine bright red tint.

Отрадна тень, пока крушин

Вливает кровь в хлороз жасмина… [3, 111].

The internal movement of the thought, experiencing the world through the contiguity of its elements and recovering patterns of the whole, comes to a standstill at homogeneity and tranquility. I deem it essential to mention the possible connection between the metaphoric image of the “night of life” and the philosophical concepts of the world as formulated by the Renaissance scholars whose opinions would determine the development of science and the collective worldview for centuries to come. Particularly, Nicholas of Cusa, whose work marked the transition from medieval to modern European philosophy, and his successors suggested that the world is infinite and that the One (which is not in opposition to anything and which encompasses all) is indivisible and cognizable through the unity of opposites. A contemporary historian of philosophy P. Gaidenko notes: “The identification of the ‘absolute top’ with the ‘absolute bottom’ is the principle which entered philosophy starting from Cusa and laid the foundation not only for the philosophy of the Early Modern period, but also for the new science taking shape in the 16th and 17th centuries. We then find this equation of the ‘highest’ with the ‘lowest’, methodologically developed in the dialectic of the ‘unity of opposites,’ not only in Giordano Bruno, but also in Spinoza, Schelling, and Hegel, that is, the most outstanding thinkers of the Early Modern period. On the other hand, the same principle is found in the mathematics of the 16th and 17th centuries, in the infinitesimal method and in the new discipline of mechanics, especially in Galilei <…>” [6]. Following Cusa’s example, G. Bruno believed that the first principle of the universe must be understood as unity where matter and form are no longer differentiated and which may be concluded to be the absolute potentiality and reality (G. Bruno, Dialogues).

Как странно слиты сад и твердь

Своим безмолвием суровым,

Как ночь напоминает смерть

Всем, даже выцветшим покровом [3, 111].

Annensky describes protagonist’s sincere amazement upon realizing that, by mentally stopping the transformations of life and its progress for the sake of knowledge, he arrived at the verge of the mystery of unity, but this peace turned into an acute sensation of emptiness surrounding him.

А все ведь только что сейчас

Лазурно было здесь, что нужды?

О тени, я не знаю вас,

Вы так глубоко сердцу чужды.

Неужто ж точно, боже мой,

Я здесь любил, я здесь был молод,

И дальше некуда?.. Домой

Пришел я в этот лунный холод? [3, 112].

In the last two poems of the trefoil, Annensky elaborates on the metaphor “a house as a soul”. In Kvadratnye okoshki [Square Windows] he draws a symbolic landscape of spiritual aspirations and an imaginary pathway of a person in a house with square windows. The physical body does not leave its cell, while the “wondering thought” has an opportunity to conquer time and space, but its way is not clear, its wings are drooping from the painful monotony of traveling («О, дали лунно-талые, / О, темно-снежный путь, / Болит душа усталая / И не дает заснуть» [3, 112]). The sign of a circle inscribed in a square («Квадратными окошками / Беседую с луной» [3, 112]) is important for the understanding of Annensky’s philosophy of suffering. The squaring of the circle is one of the best-known unsolvable scientific problems: the point is to find a way to construct a square with the same area as a given circle by using only a compass and a ruler. In this problem, mathematical calculations are not as important as finding a practical solution — using given tools to draw an actual picture. In other words, solving this problem requires keeping in touch with the realities of life. In-depth studies of the ancient Greeks, who once attempted to solve this problem, influenced their progress in the field of geometry. In 1458 Nicholas of Cusa wrote his treatise De Mathematica Perfectione [Lat., On the Perfection of Mathematics], where he reformulated the problem of squaring the circle in a different manner. He refused to give a precise definition to the equality of a straight and a curved line. Instead, he made recourse to what he used to call his vision intellectuelle [Fr., mind’s vision]; he skillfully employs geometric and arithmetic values to illustrate philosophical concepts. Cusa marked a new stage of studying the problem. A few decades later Leonardo da Vinci proposed a mechanical way of squaring the circle [See: 1, 71]. After that, even the mathematical proof of the impossibility of squaring the circle did not deter eager souls from spending years trying to find a solution. During Annensky’s lifetime, bookstores continued to receive publications whose authors still strove to solve the baffling problem (this fact is pointed out by V. Vitkovsky in the Encyclopedic Dictionary of F.A. Brockhaus and I.A. Efron, in the article Kvadratura kruga [Squaring the circle] [5]). By that time, a set phrase “squaring the circle” had long come to mean a futile and meaningless undertaking.

Annensky’s narrator – a monk and hermit – is mesmerized by a mental image, a phantom of his own imagination («Она была желаннее / Мне тайной и луной. / За чару ж сребролистую / Тюльпанов на фате / Я сто обеден выстою, / Я изнурюсь в посте» [3, 113]). He is, however, disturbed, for the continuous wandering of his thought brings him nothing but a sense of “emptiness of at the end of the day” [3, 113], while an infernal force makes him recall his carnal yearning for a woman («Ты помнишь сребролистую / Из мальвовых полос, / Как ты чадру душистую / Не смел ей снять с волос? // И как, тоской измученный, / Так и не знал потом – / Узлом ли были скручены / Они или жгутом?») and offers him a meeting with an embodied Ideal («А знаешь ли, что тут она?» [3, 113]). An attempt to lift a “living, smoke-like” veil of the beloved leads the Ideal to disintegrate.

Reconciling suffering in empirical reality with lofty ideas about life is just as problematic as squaring the circle. O. Ronen in an article on the problem of “memory” of the iambic trimeter with masculine and dactylic line endings and its semantic function in the Square Windows, recounts his impression of the poem in these words: “<…> I have never read anything scarier than Annensky, nor anything more sinister, than the Square Windows. Neither Baudelaire nor Attila József expressed the torment of the disgraced ideal, nor the doomed beauty’s way to ruin with such poignant anguish” [16]. The literary critic points out analogies between the plotline of Annensky’s poem and the story of Finn and Ludmila from Ruslan and Ludmila. He summarizes the main message of the poem as follows: “<…> it comprises the entire history of romantic sentiment. This is a late recollection of the romantic worship of an unobtainable ideal. It is also an early premonition of old age and decay, present from the outset” [16]. In his semiotic analysis of Annensky’s poetic style I. Smirnov writes that in the Square Windows, “an attempt to revive love leads to activating a line of division between the characters — the line made up of objects of a bourgeois lifestyle. The story arc culminates as the female image transforms into a grotesque male” [17, 74–75]. Е.А. Nekrasova described the denouement of the poem as the logical outcome of the “forbidden,” sinful passion [11, 74].

The above quoted researchers’ observations highlight essential facets of the poem’s meaning, but fail to reveal the significance of the main symbol — the square windows. To my mind, the poem’s imagery is derived chiefly from Goethe’s Faust. The first scene after the Prologues takes place at night in Faust’s chamber. The latter, disillusioned in his theoretical knowledge gained from philosophy, medicine, the laws, and theology, turns to magic, summons the Spirit of the Earth:

That I may detect the inmost force

Which binds the world, and guides its course;

Its germs, productive powers explore,

And rummage in empty words no more!” [Trans. Bayard Taylor]

and begs the Moon to help him break out into the “broad, free land” of life. Goethe’s description of Faust’s office includes one detail, which Annensky noticed and endowed with a broader symbolic meaning: the painted (window) panes, separating the restrained mind from the open space of free life.

Ah, me! this dungeon still I see.

This drear, accursed masonry,

Where even the welcome daylight strains

But duskly through the painted panes. [Trans. Bayard Taylor]

Annensky set the “silvery foliage” on the veil of the beloved against the “sickly peas” and “withered mignonette,” through which his narrator stares into the distance. They do not match, just as the square does not match with the circle and the ideal world with reality. Goethe’s Faust exclaims in despair:

Alas! in living Nature’s stead

Where God His human creature set,

In smoke and mould the fleshless dead

And bones of beasts surround me yet! [Trans. Bayard Taylor]

The scholar realizes that his learning would not help him understand the world and thus turns to symbols and alchemists’ magic. It is not by chance that Annensky uses a geometric sign (the squaring of the circle) and the flower symbolism in his poem. We know that medieval alchemy, which combined the knowledge of the East and the West, as well as philosophy, religion, and science, used to assign flower names to concepts based on the similarity of their Greek appellations. The protagonist’s beloved appears to him first in a hijab of “hollyhock stripes,” then in a veil of tulips. Hollyhock’s second name is musk flower, while tulip is normally associated with blood-red color of its petals. Alchemical texts are a sort of cipher: they presupposed several layers of meaning, where symbols denoted both the steps of “technological” process — changes to the primary elements of fire, water, earth, and air, and human soul’s transformations on its way to highest purity and “deification.” For instance, what we now know as an alchemical transmutation, the Alexandrians used to call metabolh. This term has two meanings: it stands for a transition from one state to another, and, simultaneously, for the mystical transubstantiation of bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood during the sacrament of the Eucharist [See: 14, 11–69; 18]. I think that Annensky’s symbols of painted panes, flowers, and the metallic epithet “silver-leafed” denote not only the monk’s recollections of the past, but also the stages of his spiritual path towards the Immaculate Bride, or the Divine Wisdom, which he went through in the course of his ascetic life. The alchemical marriage is frequently interpreted as a wedding of Christ and the Church — a heavenly analogue to the principal objective of the Great Action (human life).

The author’s irony is tangible at the end, when the poem’s protagonist discovers a hermaphrodite — a woman with “a bouncy beard” and little horns — at the final destination of his search for Eros. His intonation betrays his confusion: the monk does not know how to react to the masculine personification of his beloved.

– «Она… да только с рожками,

С трясучей бородой –

За чахлыми горошками,

За мертвой резедой…» [3, 113].

Annensky’s final verses direct us to Pushkin’s story of Finn, as well as to the image of Mephistopheles who would accompany Faust in his “practical” search for an absolute man. Annensky, who does not believe in transforming the world through pure Mind, actualizes the figurative meaning of the set phrase “squaring the circle”: it is a meaningless waste of time.

The Muchitel’nyi sonet [Painful Sonnet] presents a kind of tragic outcome of the lofty thought of the Renaissance greats. Let us mention a different, intimately psychological interpretation of this poem by L. Ya. Ginzburg (Chastnoe i obshchee v liricheskom stikhotvorenii, 1980), who rightly pointed out the “complex semantic structure” and the steady expansion of existential issues treated in this poem, where “the vivification of fire foretells its final metaphoric meaning” [8, 104]. The sonnet form endows the narrator’s impulse with importance and completeness as he boldly seeks to subject the forces of nature, to make matter serve spirit, to transform the word through art, even at the cost of his own life. This man faces a painful choice. He can strive to achieve a physical realization of the “super-substance,” which would reconcile the first elements of nature (water, fire, earth, air) and help return the original unity of opposites (“to become fire”), for God preceded any oppositions. Alternatively, he could accept a martyr’s death by fire (“to burn alive in fire”).

О, дай мне только миг, но в жизни, не во сне,

Чтоб мог я стать огнем или сгореть в огне! [3, 114].

I think that the poetic image of the new metonymic unity presented as a house — a place where the macrocosm converges on the microcosm and the particulars lead to the general (“the soul of the world”), as well as the motif of the creator’s potential fate serve as indirect allusions to the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno. Bruno’s martyrdom in 1600 on the Roman Campo de’ Fiori and his ethics of “heroic enthusiasm” and an endless love of the infinite, that elevates the creator above the routine of life and assimilates him to god, are quite compatible with Annensky’s storyline based on the tragedy of the thinking Übermensch. (Compare with the image of Ixion from Annensky’s tragedy Tsar’ Iksion [King Ixion]).

Bruno’s pantheistic natural philosophy was born out of his fascination with the work of Nicholas of Cusa, who applied to cognition a dialectical principle of coincidentia oppositorum and promoted an “apophatic theology,” deeming it impossible to define God through positive terminology. Both philosophers were convinced of the power of human reason and will over physical elements.

Мне нужен талый снег под желтизной огня,

Сквозь потное стекло светящего устало,

И чтобы прядь волос так близко от меня,

Так близко от меня, развившись, трепетала [3, 113].

The world, according to Bruno, is uniform and infinite. Its simple substance, from which a multitude of things originates, is related to the idea of internal unity of opposites (De la causa, principio, et uno [Lat., Cause, Principle, and Unity], 1584). In the infinity, the centre and the periphery are one, just as the square and the circle, matter and form, and God as a whole is represented in every single thing: “everything in everything”. The basic unit of being is a monad, which merges an object and the subject, the bodily and the spiritual. In Annensky’s imagery, individual elements, elevated by man’s dialectic reasoning to the level of highest conceptual metonymic unity, become a sort of “monads”:

Мне надо дымных туч с померкшей высоты,

Круженья дымных туч, в которых нет былого,

Полузакрытых глаз и музыки мечты,

И музыки мечты, еще не знавшей слова… [3, 113].

A fin-de-siècle thinker L.M. Lopatin, whose work Annensky treated with great respect, believed that the philosophical systems of the Renaissance had reflected an all-round worldview inspired by the revived doctrines of the Antiquity. The mystical attitude to nature filled it with “substantial forms, astral spirits and other spirit-like beings.” The richness of the human inner world was projected onto “the inner workings of the visible universe: man was seen only as the highest form of realizing those same internal forces which animated every minuscule atom. Giordano Bruno’s profound philosophical dreams give the most artistic and sophisticated expression to this strictly mystical, yet so fantastic world outlook.” [10, 20].

Thus, in search for his artistic style, Annensky the lyricist drew upon the philosophy of his time, psychology, and the European philosophy of various periods. The Cypress Casket was an attempt at an artistic response to A.N. Veselovsky’s idea of the traffic in the world literature of predicative meaningful symbols in the form of storylines and motifs reflecting man’s psychic acts and the typical forms of human living conditions [See more: 13]. Just as important for the formation of Annensky’s message and lyrical style is the poet’s immersion in the works of domestic psychological school of philology (А.А. Potebnia, D.N. Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky) [See more: 12] and works in the field of ethics and history of science (especially by his contemporary L.M. Lopatin).

Bibliography

1. Alexandrova N.V. Istoriia matematicheskikh terminov, poniatii, oboznachenii: Slovar’-spravochnik [The History of Mathematical Terms, Concepts, Signs: A Reference Dictionary]. SPb.: LKI, 2008. 248 p.

2. Annensky I.F. Knigi otrazhenii [The Books of Reflections]. М.: Nauka, 1979. 680 p.

3. Annensky I.F. Stikhotvoreniia i tragedii [Poems and Tragedies]. L.: Sov. pisatel’, 1990. 640 p.

4. Blok A.A., Nik. T-o. Tikhiie pesni [Quiet Songs] // Blok A.A. Sobr. Soch. [Collected Works].: in 8 vols. Vol. 5. M.; L.: GIKhL, 1962. Pp. 619–621.

5. Vitkovsky V. Kvadratura kruga [Squaring the Circle] // Entsiklopedicheskii slovar’ F.A. Brokgausa i I.A. Efrona [F.A. Brockhaus and I.A. Efron’s Encyclopedic Dictionary]: http://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/brokgauz_efron/50757/Квадратура

6. Gaidenko P. Istoriiia novoevropeiskoi filosofii v eio sviazi s naukoi [The History of Early Modern European Philosophy in Its Connection to Science]: http://www.gumer.info/bogoslov_Buks/Philos/Gaiden/01.php

7. Goethe I.W. Faust: in 2 parts. / Trans. A. Fet. SPb.: Izdaniie A.F. Marxa, 1889. 255 p.

8. Ginzburg L.Ya. Chastnoe i obshchee v liricheskom stikhotvorenii [The Particular and the General in a Lyrical Poem] // Ginzburg L.Ya. Literatura v poiskakh Real’nosti: Stat’i. Esse. Zametki [Literature in Search of reality: Articles, Essays, Notes] Статьи. Эссе. Заметки. L.: Sov. pisatel’, 1987. Pp. 87–113.

9. Gumilyov N.S. I.F. Annenskii. Vtoraia kniga otrazhenii [I.F. Anennsky. The Second Book of Reflections] // Gumilyov N.S. Soch. [Works]: in 3 vols. М.: Khudozh. lit., 1991. Vol. 3. Pp. 172–173.

10. Lopatin L.M. Filosofskiie kharakteristiki i rechi [Philosophical characteristics and speeches]. М.: ITs “Academia”, 1995. 328 p.

11. Nekrasova Ye. А. A. Fet, I. Annenskii. Tipologicheskii aspect opisaniia [A. Fet, I. Annensky: The Typological Aspect of Description]. М.: Nauka, 1991. 125 p.

12. Ponomaryova G.M. I. Annenskii i A. Potebnia: K voprosu ob istochnike kontseptsii vnutrennei formy v “Knigakh otrazhenii” I. Annenskogo [Annensky and Potebnya: On the Source of the Concept of Inner Form in Annensky’s “Book of Reflections”] // Uchen. zap. Tart. gos. Un-ta [Proceedings of Tartu State University]. Issue 620: Tipologiia literaturnykh vzaimodeistvii. Trudy po russkoi i slavianskoi filologii: Literaturovedenie. Tartu, 1983. Pp. 64–73.

13. Ponomaryova G.M. I.F. Annenskii I A.N. Veselovskii: Transformatsiia metodologicheskikh printsipov akad. Veselovskogo v “Knigakh otrazhenii” Annenskogo [Annnsky and Veselovsky: The transformation of academician Veselovsky’s principles in Annensky’s “Book of Reflections”] // Uchen. zap. Tart. gos. Un-ta [Proceedings of Tartu State University]. Issue 683: Trudy po russkoi i slavianskoi filologii: Literatura i publitsistika: Problemy vzaimodeistviia. Tartu, 1986. P. 84–93.

14. Rabinovitch V.L. Alkhimiia kak fenomen srednevekovoi kul’tury [Alchemy as a Phenomenon of Medieval Culture]. М.: Nauka, 1979. 392 p.

15. Rozanov V. Tchem nam dorog Dostoyevsky? K 30-letiiu so dnia yego kontchiny [Why is Dostoyevsky important to us? Towards the 30th anniversary of his death]: http://dugward.ru/library/rozanov/rozanov_chem_nam_dorog_dostievskiy.html

16. Ronen O. Ideal: O stikhotvorenii Annenskogo “Kvadratnye okoshki” [An Ideal (On Anensky’s poem “Square Windows”] // Zvezda. SPb., 2001. № 5: http://magazines.russ.ru/zvezda/2001/5/ron.html

17. Smirnov I.P. Khudozhestvennyi smysl i evolutsiia poeticheskikh system [The Artistic Meaning and Evolution of Poetic Systems]. М.: Nauka, 1977. 204 p.

18. Yuten S. Pvsednevnaia zhizn’alkhimikov v Sredniie veka [Alchemists’Daily Life in the Middle Ages]. М.: Molodaia gvardiia, 2005. 248 p.

19. Goethe J. W. von. Faust. Trans. by Bayard Taylor. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14591/14591-h/14591-h.htm#I

Julia Vadimovna Shevtchuk is a candidate of philological sciences, lecturer at the department of Russian literature and publishing of the Bashkir State University in Ufa. E-mail: julyshevchuk@yandex.ru